Não sei quantos portugueses terão ouvido falar de Ben Bradlee. Não sei mesmo se a maioria dos jornalistas estará familiarizada com a sua figura. Mas a história de Ben Bradlee confunde-se com a história dos anos mais gloriosos do jornalismo americano e, claro, com a história de Watergate.

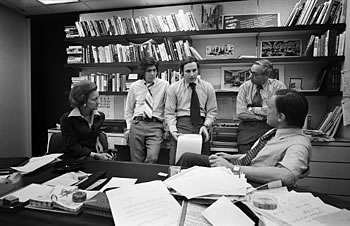

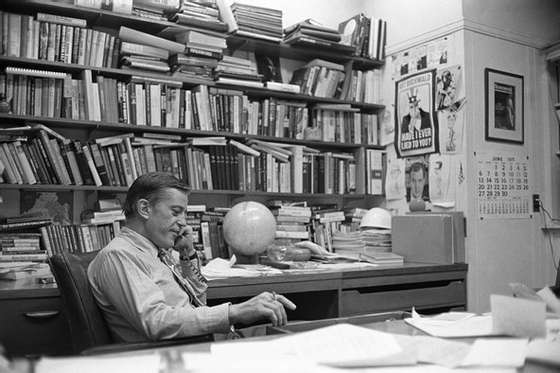

Bradlee, que morreu quarta-feira, 22 de Outubro, aos 93 anos, teve uma longa e preenchida vida – “A Good Life”, como ele titulou a sua autobiografia – foi o diretor que conduziu o Washington Post nos anos de escândalos como o dos papéis do Pentágono e de Watergate, orientando e protegendo os seus repórteres ao mesmo tempo que construía uma relação de imensa cumplicidade coma proprietária e publisher do jornal, Katherine Graham (é ela que está na foto, tal como os ainda jovens Carl Bernstein e Bob Woodward, os repórteres cuja investigação levaria à queda do Presidente Nixon; Bradlee é quem está sentado à secretária).

A primeira vez que estive no Washington Post, em 1993, o seu histórico director já tinha deixado o posto (esteve lá entre 1968 e 1991) mas o espaço da redação ainda era como no filme de Alan J. Pakula Os Homens do Presidente, de 1976, com Dustin Hoffman e Robert Redford. Três anos depois, em 1996, tive o privilégio de participar num pequeno-almoço em que ele era o convidado especial e recordo-me bem da sua perceção de que houvera um “época de ouro” dos jornais que já estava a ficar para trás. Nessa altura a Internet estava já a criar novos hábitos e novas regras.

Talvez muitos leitores do Macroscópio não percebam porque dedico a newsletter de hoje a este jornalista que em Portugal, repito, poucos conhecerão, mas faço-o porque a forma como exerceu a sua profissão é uma referência se queremos bom jornalismo e, também, uma boa democracia. É que, como ele escreveu em 1973, e se recorda no obituário do Telegraph:

“As long as a journalist tells the truth, in conscience and fairness, it is not his job to worry about consequences. The truth is never as dangerous as a lie in the long run. I truly believe the truth sets men free.”

Na New Yorker, o seu director David Remnick escreveu um Postscript onde, de alguma forma, sintetizou o que os obituários escreveram:

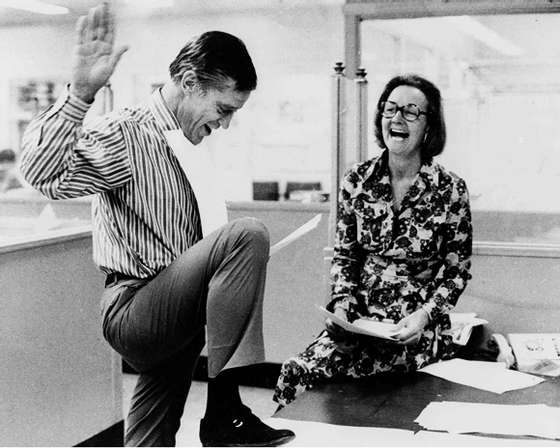

The obituaries will properly give Bradlee credit for building, along with the owner, Katharine Graham, the institution of the Post. (…) Together, Bradlee and Graham took a mediocre-to-good paper and turned it into something ambitious, wealthy, and brave. The Bradlee-Graham partnership was behind the publication (along with the Times) of the Pentagon Papers, in 1971, which made plain the extent of Presidential deception and folly during the Vietnam War. And they were behind Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein’s Watergate reporting, which led to the downfall of the Nixon Administration. Those same obituaries will cover the familiar ground of Bradlee’s close friendship with John F. Kennedy—a relationship that was, at best, deeply problematic for a journalist in his position (…), but which lent Bradlee much of his dash and glamour. (…) Even if you were quite sure he didn’t know your name, you were prepared to go to fantastic lengths to live up to his standards. And he was fun, the embodiment of how much fun journalism could be. Ben Bradlee was the least dull figure in the history of postwar journalism.

De facto, como conta Ezra Klein na Vox – What it was like to meet Ben Bradlee –, ele fazia com que as os jornalistas de sentissem diferentes, e mais importantes, quando falava com eles: “It made you feel like you were part of something, and you had better damn live up to it. The effect he had on people was extraordinary”.

Naturalmente que o Washington Post – que entretanto já não pertence à família Graham, pois foi comprado Jeffrey Bezos, o fundador da Amazon – dedicou uma ampla cobertura ao desaparecimento do seu antigo director. Desde uma sugestiva galeria fotográfica à republicação de uma comunicação que fez em 1997, de novo sobre o tema da verdade em jornalismo – “The more aggressive our search for truth, the more some people are offended by the press. The more complicated are the issues and the more sophisticated are the ways to disguise the truth, the more aggressive our search for truth must be, and the more offensive we are sure to become to some. So be it.”

Ainda no Washington Post, um antigo editor executivo, Leonard Downie Jr., recorda uma história que é enormemente reveladora do que era o espírito e as escolhas de um grande jornal e de um grande director:

When I was a young investigative reporter in the 1960s, working on a series of articles about the financial exploitation of black homeowners involving many of Washington’s then-numerous savings and loan associations, Ben made a rare appearance at my desk and asked what I was working on. With his characteristic short attention span, Ben interrupted my overly long answer to tell me that he had just met with the heads of those savings loans in his office and that they had threatened to pull all their advertising from The Post if he published the articles I was working on. I wasn’t able to breathe until he clapped my shoulder in his characteristic way and said, “Just get it right, kid.” The Post published the series, and the savings and loans pulled all their ads for a year, but neither Ben nor anyone else told me that they did. I had only been at the paper for a few years, but I knew then that I’d want to spend my entire career there.

Na Time, Jill Abramson, a anterior directora do rival New York Yimes (e a primeira mulher a ter ocupado aquele posto) escreveu que “Ben had total joie de journalism. It oozed from every pore. No one had more fun chasing a big story and no editor made the chase more fun.”

Regressando a este lado do Atlântico, destaco um texto de Marc Bassets no El Pais, “Lecciones de Bradlee”. Selecionei esta pequena passagem, muito significativa:

En tiempos en que regresa el periodismo activista —ahora reclamar la objetividad, incluso la imparcialidad, y aparcar los prejuicios en el armario parece a veces anacronía—, la lección de Bradlee es estimulante. Bradlee tenía poca opiniones e ideas. Nunca aspiró a sentar cátedra. No era de izquierdas ni de derechas, sino todo lo contrario. Se guiaba por la búsqueda de la noticia.

Parece simples, mas não é. E para que nem tudo sejam luzes, eis esta pequena nota num, em tudo o resto, muito elogioso obituário no Financial Times: “He was also sometimes criticised for not having let drop any hint of Kennedy’s sexual escapades, of which he was certainly familiar not least because one liaison was with his own then sister-in-law. Unlike now, it was the habit of those times not to report on unpresidential behaviour.”

Para terminar, uma pequena anedota sobre a perturbação que a sua simples presença por vezes gerava. Foi contada por Todd S. Purdum na Vanity Fair e revela como, um dia, esse jornalista o beijou em vez de beijar a mulher:

In the foyer, I found Ben in deep conversation with my wife, Dee Dee Myers, as the party was winding down, and the house was emptying. In a dyslexic faux pas, I reached over to pump her hand, and leaned in to kiss his lips. He kissed me right back and then reeled. “Wow!” Sally, approaching from the corner, asked, “What about me?”

Bradlee gostava de histórias, como todos os jornalistas e editores, e adoraria, estou certo, ler esta pequena história sobre ele mesmo. Recordá-lo-emos como uma grande referência.

(Todos os dias, ao fim da tarde, o Observador distribui a newsletter Macroscópio, um texto como este que eu próprio preparei ao longo do dia. Nela se reúne o melhor que a imprensa, portuguesa e internacional, publicou sobre o tema escolhido. Tal como neste exemplo, os textos são reproduzidos na língua em que foram escritos. Se quiser receber diariamente na sua caixa de email o Macroscópio, ou qualquer outra das newsletters do Observador, basta-lhe deixar aqui o seu endereço electrónico.)

Siga-me no Facebook, Twitter (@JMF1957) e Instagram (jmf1957).