Graças a deus que existem cidades antigas, em cujos centros históricos é difícil instalar um supermercado, porque é assim que sobrevivem as mercearias.

Estão abertas durante 12 horas por dia, 6 dias por semana, à espera que eu me lembre das coisas de que me esqueci.

Depois de umas poucas de visitas à mercearia, a Dona Ana começou a mandar-me ir buscar coisas por mim própria, mesmo nas áreas que ficam por detrás do balcão, quando lhe acontece estar ocupada com outro cliente. Se a encontro sentada num degrau ao fundo da loja, a fazer as suas contas, posso deixar as moedas certas para pagar os ovos que tirei da divisão misteriosa ao lado da mercearia.

O frigorífico barulhento chocalha e geme todo o dia com a sua seleção estranha de manteigas, iogurtes, vinhos e refrigerantes, ao lado do congelador onde residem quantidades vastas de lulas congeladas e esparregado. Está sempre escuro dentro da mercearia e os nossos olhos precisam de uns segundos para se habituarem. Nos dias de calor, está ainda mais escuro, graças a uma persiana estendida por cima da porta, de modo que a fruta, nas prateleiras de mármore logo à entrada, não se estrague.

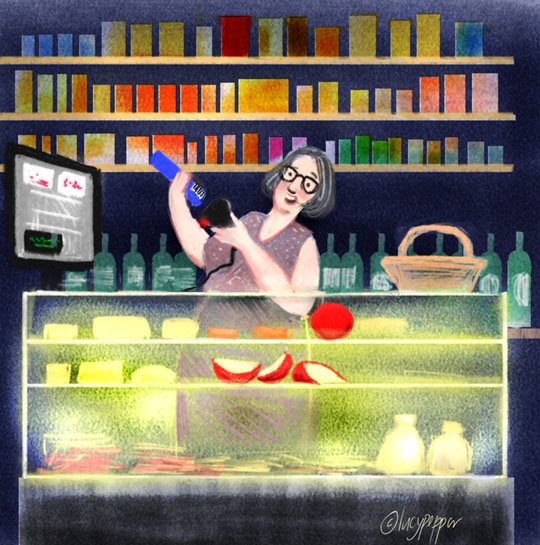

O balcão frigorífico com os produtos frescos — queijos bons de leite de ovelha, queijos maus de tipo flamengo, e pacotes aleatórios de bacon e presunto — oculta o lugar secreto onde a Dona Ana guarda os enchidos. Pelos enchidos, tem se de perguntar. A Dona Ana sugere as versões mais baratas de bolachas, para o caso de eu estar interessada. Atrás do balcão, está a caixa registadora, uma daquelas caixas novas onde tem de se bater no écran com o dedo, categorizando cada coisa, ou passar o código de barras pelo scanner. Ela ri-se, porque a máquina só lê bem os produtos metade das vezes.

Há um banco de plástico para quem precisa de se sentar. Durante várias horas do dia, está sempre uma senhora idosa sentada no banco, à espera de que a Dona Ana acabe de percorrer as prateleiras à procura do que ela precisa. As clientes sentam-se e contam histórias das suas consultas no hospital ou dos problemas dos seus netos na escola, ou simplesmente sentam-se, exaustas pelo calor, olhando para os turistas que entram e pedem coisas em espanhol básico porque não leram aquela parte do guia turístico que explica que aqui não é Espanha e que deviam tentar falar Português básico.

A Dona Ana é a guardiã das fofocas, e quase todas as fofocas são sobre doenças graves ou sobre mortes. Quando entro na mercearia, encontro-a sempre a conversar sobre um assunto qualquer com alguém, e depois da pessoa sair, continua a história comigo, sem voltar ao início, como se eu tivesse conhecido o Sr. João (aquela com a perna esquisita e uma filha em Angola, e que morreu a semana passada) toda a minha vida.

Há um cesto de algas para sushi no chão, ao lado do banco. Há latas de “baked beans” ingleses na prateleira, ao lado das de feijão frade, e que compro nos dias maus, quando preciso do conforte de uma comida da minha terra. “Porque vende isto?”, perguntei um dia. “Ah, há pessoas daqui que foram lá fora e voltaram a gostar disso … são muito populares”. Quem sabe?

As mercearias já estão mais ou menos extintas na aldeia suburbana onde eu vivia antes de me mudar para Lisboa. Em dez anos, quatro supermercados apareceram e limparam do mapa todas as lojas, menos as mais teimosas. A mercearia que sobreviveu perto da minha casa foi uma bênção durante os meus primeiros anos em Portugal. Não por causa dos produtos que vendia, mas por me ter ajudado a tornar-me parte da comunidade.

É na mercearia que ficamos à espera para ser atendidos, e enquanto esperamos, ouvimos e aprendemos. Ouvimos as bisbilhotices, aprendemos os nomes das pessoas, tornamo-nos numa cara que as pessoas começam a conhecer, dizemos olá aos bebés e vemo-los crescer, descobrimos um vocabulário novo, e passamos a figurar na vida local. Aprendi a falar português com maior fluência devido ao muito tempo que passei à espera na mercearia e descobri muita coisas sobre como as pessoas vivem, o que fazem com os ingredientes que compram, como lidam com os seus problemas — muito mais do que teria aprendido a empurrar um carrinho num supermercado.

Na minha rua em Lisboa, há três mercearias, um talho e uma papelaria, e dentro de cada uma delas, pode-se conversar, brincar e ter a oportunidade de começar pertencer a uma comunidade.

E quando a patroa da mercearia aprende o nosso nome e se lembra de o usar na nossa visita seguinte, ficamos a saber que somos de cá.

An ode to the mercearia.

Thank heavens for old cities, where it is hard to find a space to stick a supermarket in the city centre, for that is how the mercearia survives.

She is there 12 hours a day, six days a week, waiting for me to remember what I forgot.

After just a few visits, Dona Ana began to tell me to go and get things for myself, even from behind the counter if necessary, when she was busy with someone else. If she is sitting on a step at the back of the store, doing her accounts, then I can leave her the right money for the eggs that I have found in the mysterious side room.

The noisy fridge cabinet rattles and groans all day with its odd selection of butters, yoghurts and wine and fizzy drinks, next to the freezer cabinet which contains vast quantities of frozen squid and creamed spinach. It is already pretty dark inside the mercearia and it takes a minute for your eyes to adjust. To make it even darker, a blind is clothes-pegged over the front door on hot days to prevent the sun ruining the fruit that sits on marble shelves built into the walls just inside the door.

The refrigerated counter with its cheeses, good sheep cheese and bad sliced flamengo, and random packs of cuts of bacon and presunto belie the secret place where she keeps the chouriços. You have to ask for those. She will offer you the cheaper versions of biscuits, just in case you like them. Behind the counter is the cash register, the new kind where you bash the screen with your knuckle, categorising everything as you go, or scan it with a barcode scanner. It makes her laugh because it only reads the codes properly half of the time.

There’s a plastic stool for anyone who needs it to sit down, and, for much of the day, there is one old lady or other sitting on it, waiting while Dona Ana shuttles around the shop, finding things for her. The ladies sit and tell about their latest hospital visit or their grandchild’s problems at school, or they just sit, exhausted from the heat, looking at the tourists who come in to ask for things in pidgin Spanish because they forgot to read the guidebook that tells them that this is not Spain and that they should try to speak pidgin Portuguese.

She is the keeper of all the gossip, and almost all of the gossip is about the latest grave illness or death. She will be discussing it with someone as I walk in and, when that someone has left, will continue telling the story, without restarting it, to me, as if I have known Sr. João (the one with the gammy leg and a daughter in Angola, who died last Thursday) all my life.

There is a basket of sushi seaweed next to the stool. There are English baked beans on the shelves next to the black eyed beans, which I can go and buy on a bad day when I need comfort food. “Why on earth do you sell these?” I once asked. “oh, there are people round here who went there and came back with a taste for them… they’re very popular”. Who knew?

She is the keeper of the emergency herbs. I run in at the end of the day “do you have any coriander?” There’s none visible. “of COURSE!” and hands me a bunch from the mysterious side room into which I only usually venture for the eggs which are just inside the door. “How much do I owe you?” and she waves me off.

Mercearias were all but gone in the suburban village where I used to live. In the space of ten years, four supermarkets were built and wiped all but the most stubborn off the map. The one that remained near my house was a godsend to me in my early years in Portugal. Not for the things it sold, but for helping to make me part of the community.

It is in the mercearia that we have to stand and wait to be served, so we stand and wait and hear and learn. We hear the gossip, we work out what people’s names are, we become a face that people start to recognise, we say hello to tiny kids and watch them grow up, we learn new vocabulary and vernacular, we become a part of things. I learned to speak more fluently because of my time standing around in the mercearia and I learned more about how people lived, how they did things with the ingredients they took home, how they dealt with their problems, than I ever did pushing a trolley round a supermarket.

In my street in Lisbon, there are three traditional mercearias and a butcher and a papelaria, and inside each of them you can chat and joke and get the chance to start to belong.

And when the boss of the mercearia learns your name and remembers it for next time, you know you have arrived.